James Webb Space Telescope reveals largest-ever panorama of the early universe

"I don't know if the James Webb Space Telescope will ever cover an area of this size again."

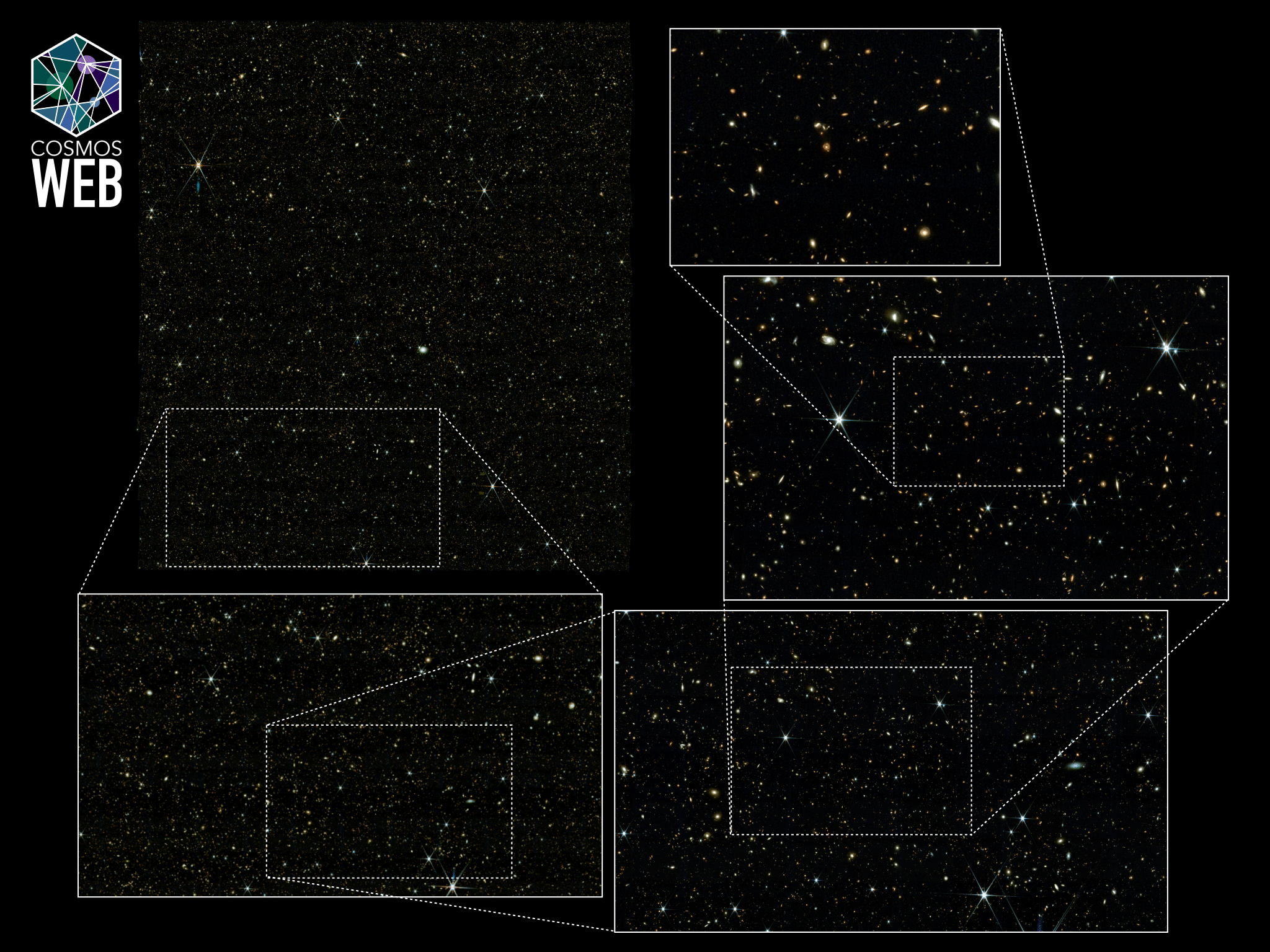

Astronomers using the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) have unveiled the largest map of the early universe to date, a sweeping cosmic panorama that offers seasoned scientists and curious stargazers alike a front-row seat to the ancient cosmos.

The images come from COSMOS-Web, the largest observing program the James Webb Space Telescope undertook in its first year. It surveyed a patch of sky equivalent to the width of three full moons placed side-by-side, the telescope's widest observation area to date. The survey stitched together more than 10,000 exposures, revealing nearly 800,000 galaxies, many of which shine from the universe's earliest eras. Harnessing the abundance of data that came from this effort, on Thursday (June 5), the team released the largest contiguous image ever captured by the JWST, along with a free, interactive catalog detailing the properties of each galaxy — a cosmic record that's as vast as it is richly detailed.

"I don't know if the James Webb Space Telescope will ever cover an area of this size again, and so I think it'll be a good reference and a good data set that people will use for many years," Jeyhan Kartaltepe, an astrophysicist at the Rochester Institute of Technology in New York and the lead researcher of COSMOS-Web, told Space.com. "The hope is that, now, anybody at any institution can make use of this data for their own science."

When the JWST launched in 2021, the global COSMOS-Web team comprising nearly 50 researchers from institutions around the world was awarded over 200 hours of observation time, the most allocated to any project in the telescope's inaugural year. While many JWST studies zoom in on small, deep slices of sky, COSMOS-Web prioritized breadth, capturing a wider cosmic canvas that brought to light 10 times more galaxies than astronomers anticipated from these early epochs.

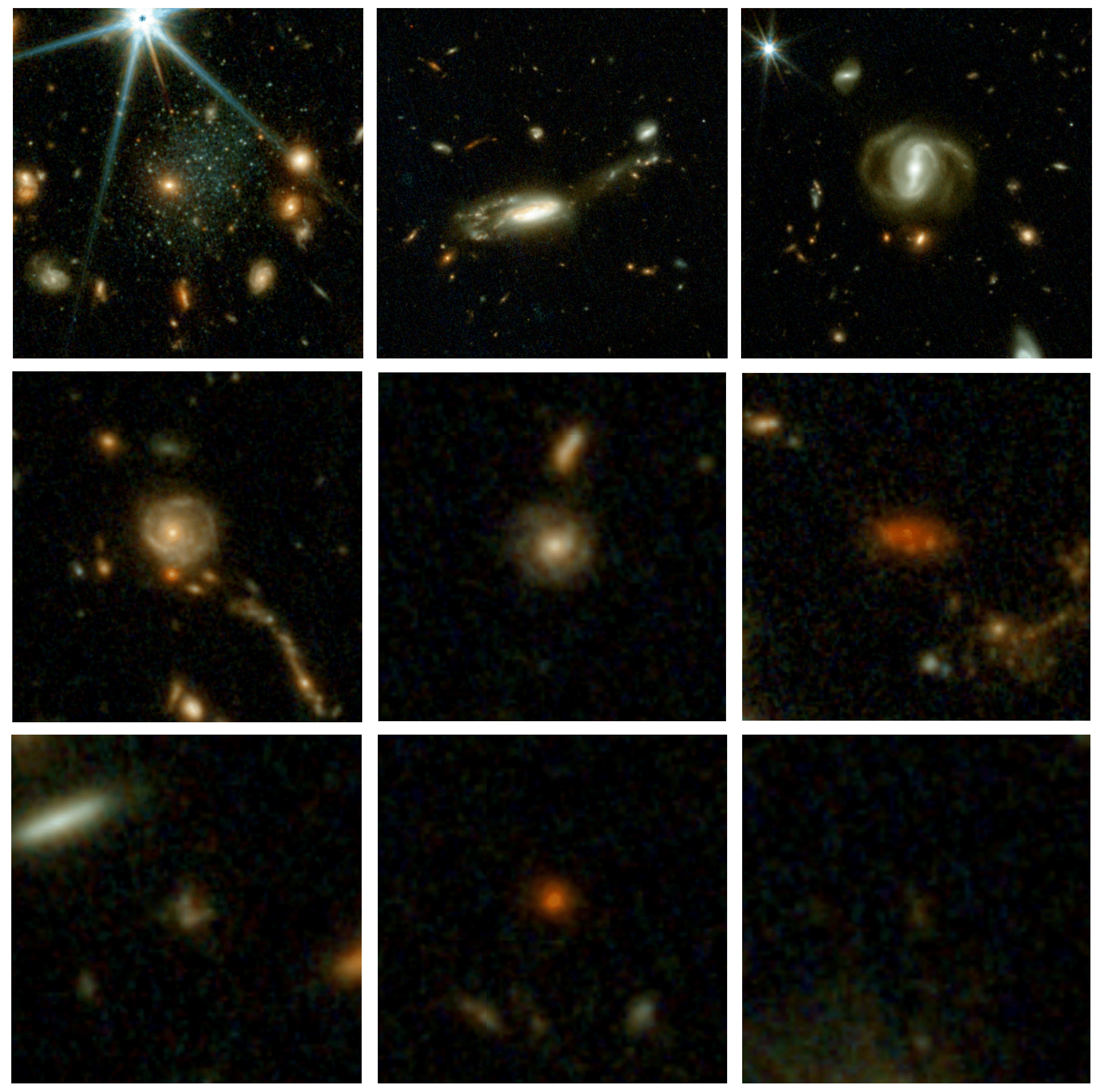

"It was incredible to reveal galaxies that were previously invisible at other wavelengths, and very gratifying to finally see them appear on our computers," Maximilien Franco, postdoctoral researcher of astrophysics at the University of Hertfordshire in the U.K., said in a statement.

The JWST's expansive view allows astronomers not only to catalog distant galaxies, but also to study how their characteristics — including size, shape and brightness — are shaped by their cosmic environments, such as whether they reside in isolation or in crowded regions. "That tells us a lot about what influenced them as they evolved," Kartaltepe said.

Alongside the catalog, the COSMOS-Web team has published a series of scientific papers exploring the data. One study, posted to the preprint archive arXiv on Wednesday (June 4), examines the most luminous galaxies at the centers of galaxy groups, tracing how their structure and star forming activity have co-evolved over the past 12 billion years.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

A key science goal of the project was to map the earliest structures during the Reionization Era (which fell more than 13 billion years ago) when the first galaxies ignited and began clearing the thick hydrogen fog that blanketed the early cosmos. To achieve this, Kartaltepe and her team plan early galaxies as tracers to measure the size of "reionization bubbles," vast regions where light from stars and galaxies carved clearings in the primordial haze.

"That's not something we finished yet," Kartaltepe said. "But that was the main goal, and something that we're really excited about."

Another paper, which was also posted to arXiv on Wednesday, tests a machine learning technique that can estimate the physical properties of galaxies in the massive dataset. The team also developed a new method to measure the brightness of distant galaxies more accurately. Unlike traditional techniques that simply sum the light within a fixed area, this approach models how light is spread across a galaxy, enabling more precise measurements that allow researchers to combine JWST images with blurrier ground-based data without losing important details.

Three more studies detail the team's data processing efforts over the past two years, a meticulous process involving aligning and cleaning more than 10,000 individual images. As a brand-new observatory, the JWST brought unexpected challenges. The telescope's images included unforeseen artifacts, such as noise patterns and distortions, which the team had to carefully correct.

Despite these hurdles, the JWST outperformed pre-launch models predicting how faint or distant galaxies it could detect, said Kartaltepe. "The reality turned out to be better — we were able to go deeper than what we expected."

The catalog holds "incredible potential," she added.

"There's still so much we don't know."

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Sharmila Kuthunur is a Seattle-based science journalist focusing on astronomy and space exploration. Her work has also appeared in Scientific American, Astronomy and Live Science, among other publications. She has earned a master's degree in journalism from Northeastern University in Boston. Follow her on BlueSky @skuthunur.bsky.social

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.