A whole 'population' of minimoons may be lurking near Earth, researchers say

"If there were only one object, that would be interesting but an outlier. If there's two, we're pretty confident that's a population."

Earth's minimoon may be a chip off the old block: New research suggests that 2024 PT5 — a small, rocky body dubbed a "minimoon" during its discovery last year — may have been blown off the moon during a giant impact long ago, making it the second known sample traveling near Earth's orbit.

The discovery hints at a hidden population of lunar fragments traveling near Earth.

"If there were only one object, that would be interesting but an outlier," Teddy Kareta, a planetary scientist at Lowell Observatory in Arizona, said in March at the 56th annual Lunar and Planetary Sciences Conference in the Woodlands, Texas. "If there's two, we're pretty confident that's a population."

A new kind of evidence

Earth travels through and with a cloud of debris as the planet makes tracks around the sun. Some of that material is human-made — satellites and space junk. Other material is rocky debris left over from collisions in the early solar system. These near-Earth objects (NEOs) can be a concern, so they are tracked to ensure they are not a threat to our planet.

Related: Just how many threatening asteroids are there? It's complicated.

In August 2024, astronomers in South Africa identified a new rock, known as 2024 PT5, traveling near Earth. 2024 PT5 was moving slowly, with a relative velocity of only 4.5 mph (2 meters per second), making it a strong target for the Mission Accessible Near-Earth Object Survey (MANOS). Only nine other asteroids have been seen traveling so slowly at their closest approach.

Kareta, along with MANOS principal investigator Nick Moskovitz, also at Lowell, have been intrigued by the idea of finding moon rocks in space since just after the first such fragment was identified in 2021. MANOS is designed to hunt for and characterize the near-Earth asteroids that might be the easiest to visit with a spacecraft. According to Kareta, that meant the survey was ideal for looking at lunar castoffs. Within a week of 2024 PT5's discovery, they had turned the Lowell Discovery Telescope in the space rock's direction.

Get the Space.com Newsletter

Breaking space news, the latest updates on rocket launches, skywatching events and more!

After studying 2024 PT5 in both visible and near-infrared data, they concluded that it wasn't an ordinary asteroid. Its composition proved similar to that of rocks carried back to Earth during the Apollo program, as well as one returned by the Soviet Union's Luna 24. The researchers also found that 2024 PT5 was small — 26 to 39 feet (8 to 12 meters) in diameter.

Kareta and his colleagues suspect that 2024 PT5 was excavated when something crashed into the moon. By studying the asteroid's composition, they hope to tie the material back to its source and perhaps even identify its parent crater.

Cratering events are one of the most important processes that shape planetary bodies without tectonics or liquids to remold them. But impacts can be affected by a variety of variables, and understanding them can be a challenge. Matching debris to its crater can provide another way to understand what happens when two bodies collide. That's what makes identifying lunar rocks in space so intriguing.

"It's like realizing a crime scene has a totally new kind of evidence you didn't know you had before," Kareta told Space.com by email. "It might not help you solve the crime right away, but considering the importance of the task, new details to compare are always welcome."

Changing lanes

Material from the Earth-moon system should be some of the easiest to fall into orbit near Earth. After an impactor collides with the moon, all but the fastest-moving material flung into space should continue traveling near our system. Although 2024 PT5 was dubbed a minimoon in September, it only briefly fell in line with the planet.

Kareta compared it to two cars on the highway. Earth is blazing along in its own lane, while 2024 PT5 chugged along the interior path, closer to the sun. In 2024, the tiny chunk of rock changed lanes, falling into Earth's path at roughly the same speed. By the end of September, it had moved on, shifting outward. Earth left it behind, but on the solar race track, the pair should be parallel again in 2055, scientists estimate.

2024 PT5 is the second lunar fragment identified by researchers. Another small rock, Kamo'oalewa, was traced to the moon in 2021, five years after its discovery. That could hint at a new population, hidden in plain sight.

Both objects are traveling in Earth-like orbits, but they don't have much else in common. Kamo'oalewa is larger and appears to have been battered by cosmic rays, solar radiation and other processes longer than 2024 PT5 has. That might suggest it has been in space longer, Kareta said.

Their orbits are also a bit different. Kamo'oalewa's quasi-satellite orbit keeps it in Earth's immediate vicinity for several consecutive orbits, even though it isn't actually spinning around the planet. Unlike the lane-changing 2024 PT5, Kamo'oalewa is more like a car that stays one lane over, moving at roughly the same speed.

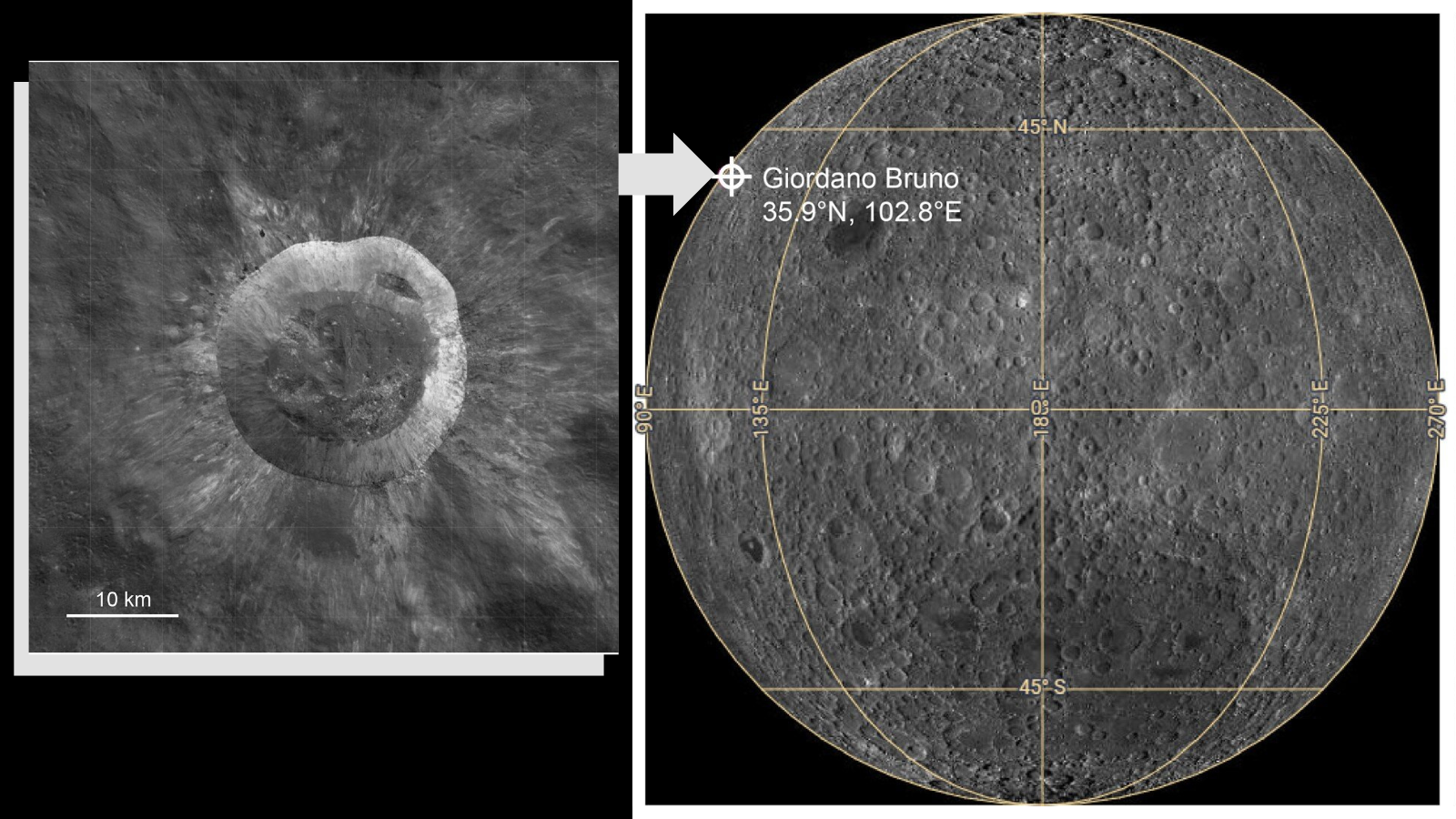

Researchers are trying to match Kamo'oalewa to a crater. A recent study suggested that it could have come from a smashup that created Giordano Bruno crater, a 14-mile-wide (22 km) impact basin on the far side of the moon.

Kareta is hopeful that more will be identified. While a single sample is an oddity, two could be part of a crowd. He suspects that some asteroids that have been identified as unusual may be lunar rocks in disguise.

When the orbits of NEOs are calculated, their source region is often estimated based on their current travels. If some objects have been misclassified and their sources are incorrect, that could mean other aspects of their orbits are misunderstood. Although that could potentially increase the long-term chances of Earth being hit by an asteroid, Kareta said it is "almost certainly not" the case, "but we'll need to prove it."

For now, Kareta and his colleagues will continue to use MANOS to search for other potential lunar fragments. He's hopeful that the doubled population will convince other researchers to take a closer look, too. Upcoming large-scale surveys — like the Vera Rubin Observatory, a ground-based telescope expected to see first light this year — should also help to reveal other dim objects.

The research was published in January in The Astrophysical Journal Letters.

Join our Space Forums to keep talking space on the latest missions, night sky and more! And if you have a news tip, correction or comment, let us know at: community@space.com.

Nola Taylor Tillman is a contributing writer for Space.com. She loves all things space and astronomy-related, and always wants to learn more. She has a Bachelor's degree in English and Astrophysics from Agnes Scott College and served as an intern at Sky & Telescope magazine. She loves to speak to groups on astronomy-related subjects. She lives with her husband in Atlanta, Georgia. Follow her on Bluesky at @astrowriter.social.bluesky

You must confirm your public display name before commenting

Please logout and then login again, you will then be prompted to enter your display name.